Press Releases |

Shadow Creek Ranch 20 years later: How a unique partnership paved the way for development

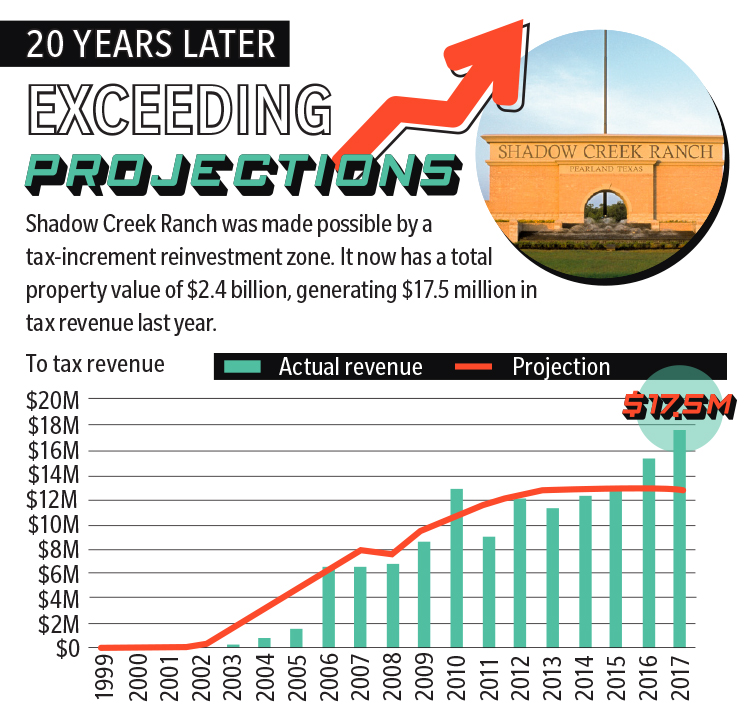

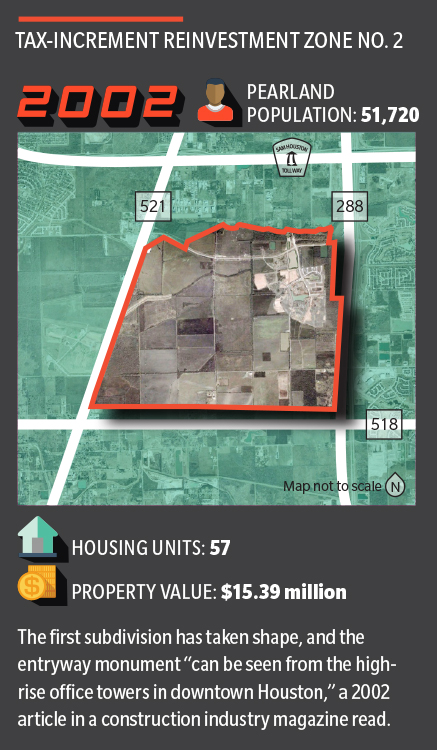

Shadow Creek Ranch was made possible by a tax-increment reinvestment zone. It now has a total property value of $2.4 billion, generating $17.5 million in tax revenue last year.

In the mid-1990s, Carlo Ferreira, a Las Vegas developer, was invited to Houston to look at the emerging opportunities in the area. With development already cropping up around the city, Pearland caught his eye.

“This is where the opportunity lies,” Ferreira said. “I liked the market, and that it was growing.”

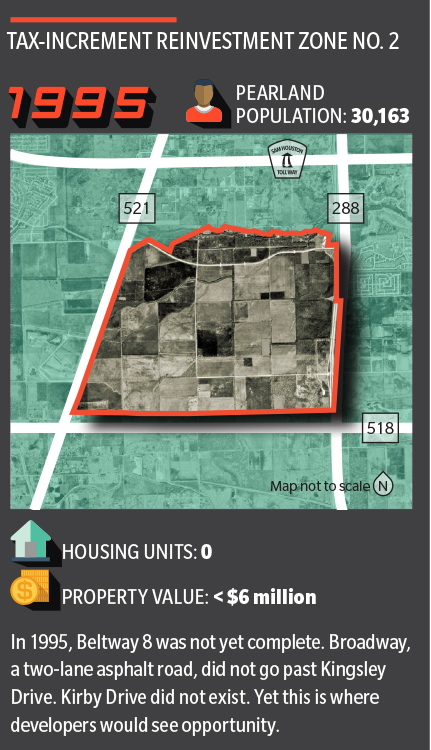

There was one problem: The land he had in mind, some 6 square miles, was nowhere near ready to be developed.

The solution to that problem—the creation of a special taxing entity that has since collected $134 million in revenue—was officially enacted 20 years ago this December.

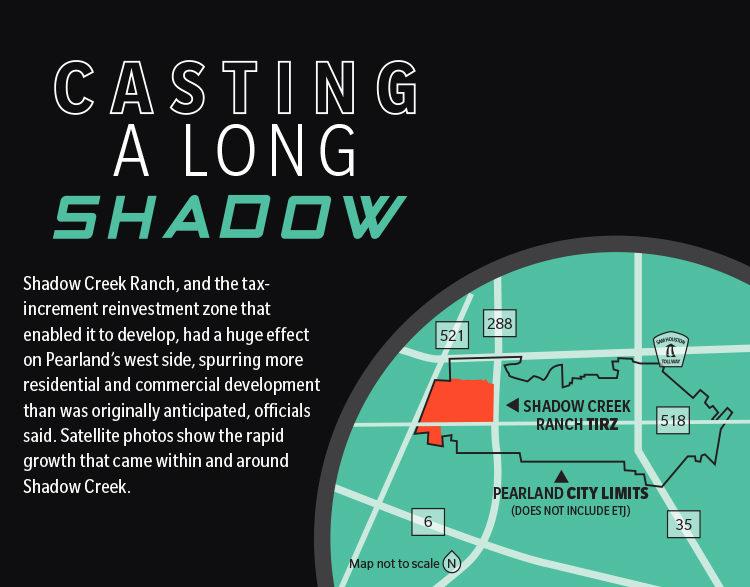

The tax increment financing zone, Pearland TIRZ No. 2, is one of the largest such entities in Texas with over 3,900 acres. It is also a public-private partnership that is paying long-lasting dividends, city officials and developers said, with property values now in excess of $2.4 billion. But most people know of this area by another name: Shadow Creek Ranch.

Wrangling the ranch

In January 1998, with his sights set on building a massive master-planned community in Pearland, Ferreira dispatched a team of brokers to begin buying up property on the west side of Hwy. 288. Coincidentally, one of the landowners was Mavis Kelsey, co-founder of the Kelsey-Seybold Clinic. Years later, the firm would buy back some land for two facilities.

The land grab stretched from FM 521 on the west side to Hwy. 288 on the east, with FM 2234 as its northern border and Broadway Street at the south. The property value at the time was around $6 million, he said.

As he made land deals, Ferreira and colleague Gary Cook worked with city officials to negotiate the TIRZ. The suggestion that the city create a special taxing entity to help the development raised eyebrows, said Alan Mueller, then-deputy city manager of Pearland.

“This one, because it was so big … it generated a lot of interest,” Mueller said. “People had this notion the city was giving away all this money to the developer … and that’s not the case.”

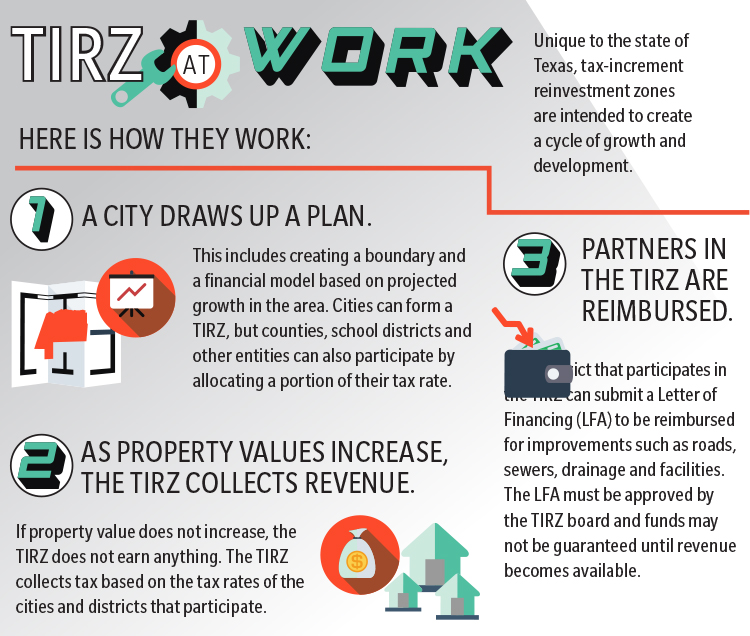

Under Texas law, an incorporated city can create a TIRZ to encourage the redevelopment of an area that might not otherwise thrive on its own. A TIRZ can help build roads, sewers and other public facilities.

A TIRZ captures a portion of property taxes from a geographic area—but only from the growth in property value compared to the zone’s base year. For example, if land starts at a value of $100,000, and after being inside the TIRZ for one year, the value increases to $110,000, the TIRZ captures only the taxes on the $10,000 increase.

“That’s the key thing—the developer has to put up all of the money to build everything,” Mueller said. “And they’re at risk until the value builds up enough to be reimbursed.”

Untouched by developers and far outside Pearland city limits, Shadow Creek would need hundreds of millions in infrastructure, Ferreira said.

“We spent between $25 [million]and $50 million in infrastructure just to produce the first lot,” he said.

The developers funded the extensions of Kingsley and Kirby drives and Broadway Street, and built much of the water, sewer and drainage systems, which had benefits outside the development itself, Mueller said.

“As part of the deal we worked out … the excess storm water runoff from Clear Creek enters their system. When they ran the hydrology models, the surface water elevation at Hwy. 288 actually went down after Shadow Creek was built,” Mueller said, meaning there was a net benefit to the watershed. “It’s part of the quid pro quo—we’d say, ‘We will help with the TIRZ, but you’ve got to help with drainage.’”

Other entities can participate in a TIRZ by contributing a portion of their property taxes. Brazoria County, Fort Bend County and Alvin ISD signed on, seeing that it would assist with infrastructure and result in higher tax revenues than would have occurred if the area had developed in a more piecemeal fashion, Mueller said.

For Alvin ISD, it was instrumental in preparing for the eventual growth of the school district, officials said.

“The TIRZ agreement has provided Alvin ISD with a financial benefit that has, over the years, assisted with the costs associated with school construction as well as operations of the campuses,” AISD Assistant Superintendent Daniel Combs said.

Under its TIRZ participation, AISD receives annual refunds of some of its captured taxes, which is advantageous under the state’s school funding formula, Mueller said. However, state law changed in 1999, making Alvin the last school district to be able to take advantage of this benefit.

Residential, commercial booms

Diane Smith, 57, had her eye on Shadow Creek Ranch for about a year before deciding to buy in 2003.

“I remember driving down sometime on [Hwy.] 288. It was just land as far as you can see. There was nothing there. Then one day driving down, there was this little community coming up,” Smith said.

She found a house for her, her mother and her brother in Lakeside Terrace. Being close to the Texas Medical Center was a big draw, she said, but the home itself, priced at $214,000 with large bedrooms and home-office space, was ideal.

“It’s great for work, relaxation and just good place to live,” Smith said. “I can’t believe how much it changed.”

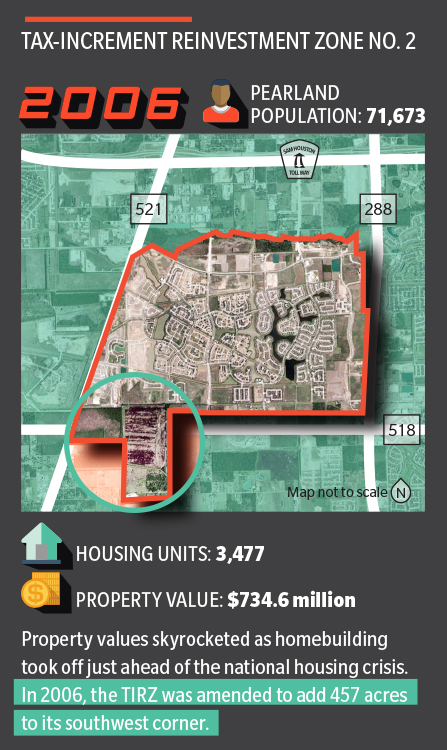

By 2005, the development was building 1,000 homes a year. When the 2008 housing crisis hit, the rate of growth slowed but did not stop, Ferreira said.

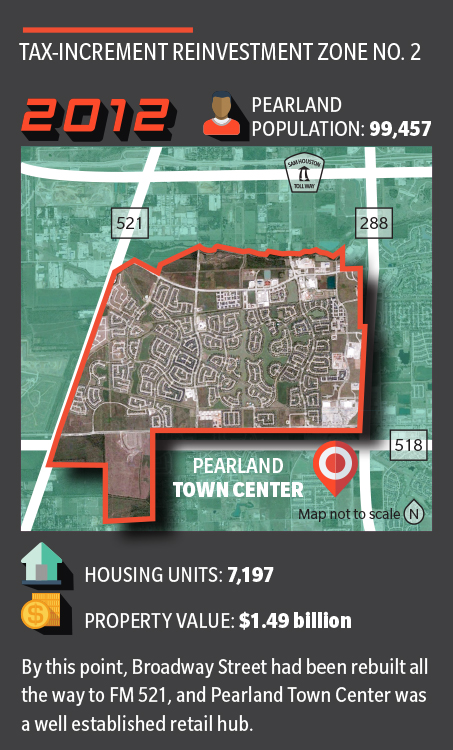

Allen H. Crosswell, who oversees the commercial and multifamily portfolio for Shadow Creek, said a second boom came as two hospitals, a Kelsey Seybold clinic and administration building, and Pearland Town Center opened in a span of just a few years, around 2011 to 2013.

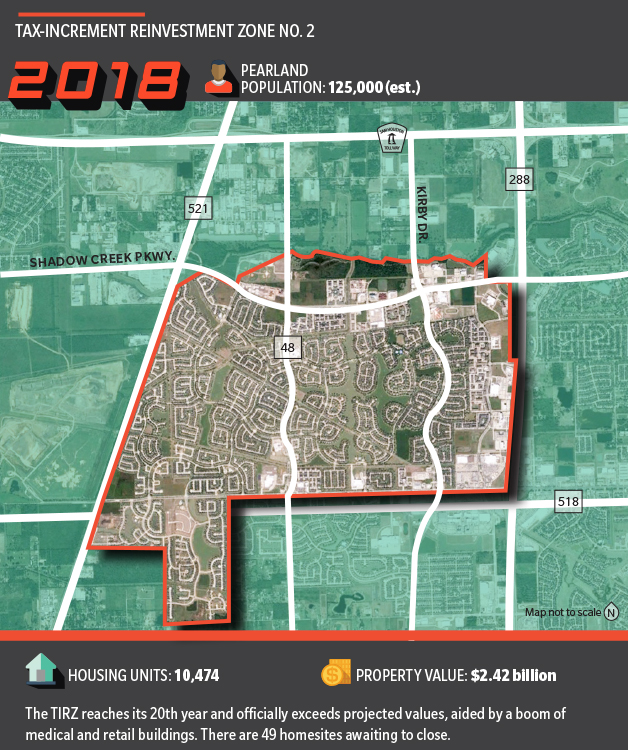

“I think you will see a little more medical coming in, and other commercial,” he said. “There’s only about 70 acres left. I think we’ll be out of inventory by 2019.”

Officials agree that the end result rapidly transformed Pearland.

“Pearland was great the way it was, but we knew that if we didn’t do something like this, we’d end up with a bunch of hodge-podge stuff no one would be proud of,” Mueller said.

Pearland City Manager Clay Pearson, who came to the job in 2014, said the development made the city more competitive as well.

“This allowed Brazoria County, Beltway 8/Hwy. 288 area to participate in some of the region’s growth on a larger scale,” Pearson said.

The next 10 years

As of 2016, the TIRZ exceeded its projected build out value at $2 billion, then reached $2.42 billion in 2017. From here on out, the TIRZ board is conservatively estimating that growth will plateau, but it is possible it could reach close to $3 billion, Mueller said.

Higher values means more tax revenues will be available to reimburse projects in the zone.

This summer, the city of Pearland received approval for $60 million to build a library, a fire station, a park expansion and other improvements—projects that otherwise would have required the city to take on more debt—that will be eligible for reimbursement from the TIRZ. A design contract for the library is underway, with construction slated for 2020.

By design, the TIRZ will wind down in 2028, meaning each taxing entity will revert to collecting its full tax revenue, and any remaining funds in the TIRZ account after all outstanding obligations are covered will be returned to each participating district, Mueller said.

For Pearland, winding down the TIRZ will not necessarily mean a big increase in operating revenue. Part of its TIRZ contribution is paid back every year as an administrative fee that goes into the city’s maintenance and operations budget, Pearson said. When the TIRZ shuts down, this fee will go away, and the property taxes coming in will be split with debt service.

“It’s so far off, we don’t know what it will look like yet, but we are starting to have that conversation,” Pearson said.

As the last few homes await to be built and sold, closing a chapter for Shadow Creek Ranch, Ferreira’s development company has received approval on plans for a similar project, Aurora Highlands in the Denver metropolitan area.

“Chapter 2 of what happened here is happening there,” Ferreira said.

Shadow Creek Ranch, then and now

Click here to and then scroll to bottom to sse the slider to compare a 1995 satellite photo of west Pearland compared to 2018. Shadow Creek Ranch development can be seen to the left of Hwy. 288, which runs down the middle of the image.